THE THINGS OF LIGHT, 2008

This collection of paintings, drawings, and prints comes out of two years spent looking at one long, troubled reach of water. The Hanford Reach is the last free‑flowing section of the Columbia River left in the United States, a strip of river that runs swift and unbroken through the Hanford Site in south‑central Washington. That stretch of land—586 square miles of sage and sand and wire—was built up in 1943 to make plutonium for nuclear weapons, including the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, where more than eighty thousand people died. The site kept working for decades, sending out iodine‑131 plumes that drifted downwind and lodged in the bodies of people who never saw the inside of a reactor, and its waste still seeps toward the Columbia, entering fish and, through them, the people who eat from the river.

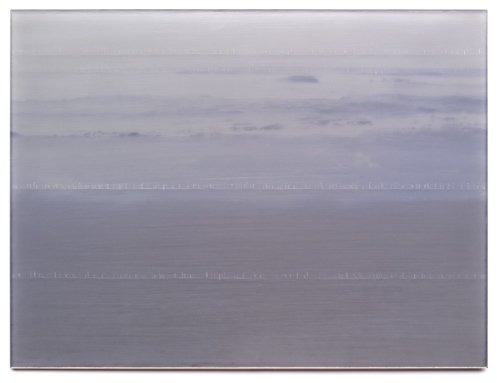

The prints begin with time‑lapse photographs of the Hanford Reach and the mouth of the Columbia, the camera watching as light changes and the water works past, hour after hour. Onto these shifting images, layers of text are added: fragments of stories told by Nagasaki survivors, numbers and reports about the environmental and health cost of the work at Hanford, and lines from poems by Dylan Thomas and Mary Oliver. The words lie like sediment on the riverbed of the image—some sharp and legible, others blurred by time and motion. They carry grief, warning, praise, and hard fact all at once.

The paintings are built differently but keep to the same river. Digital transparencies of places near the Columbia’s mouth and around the old reactor sites are laminated between glass and mirror, so that light can move through and rebound from within. Over this, roughly twenty layers of paint are laid down on the glass, with text inscribed, carved, or buried between coats. With each layer, the surface thickens; with each cut of text, it opens again. The process is slow and repetitive, as if the painting had to live through its own half‑life before it was finished. What finally shows on the surface is only a fraction of what has been written and covered, said and unsaid.

The work is an attempt to stand inside a dark chapter of history and see how it has marked the place that is now home. The river that once cooled reactors now carries their legacy; the land that held secrecy now holds memory; the people who live along the Columbia, the artist included, move daily through a landscape shaped by decisions made in war and maintained in quiet. These pieces do not claim to heal that past or explain it away. They are meant as stations for reflection, small fields of light and shadow where a viewer might pause long enough to feel the weight of what happened and to ask what kind of future could be made in full view of it.